Suri, also known as the Surma people live in the southwestern plains of Ethiopia. They raise cattle and farm when the land is fertile. Cattle are important to the Suri, giving them status. The more cattle a tribesmen has, the wealthier they are. In order for a man to marry a woman in the Suri tribe, he must own at least 60 cattle. Cattle are given to the family of the woman in exchange for marriage. Like the other tribes, the Suri will use the milk and blood from the cow. During the dry season, the people will drink blood instead of milk. Blood can be drained from a cow once a month. This is done by making a small incision in it’s neck.

The Suri are very much like the Muris tribe and practice the same traditions. The women wear lip plates that are made out of clay. The men in the tribe fight with sticks called Dongas. Both the men and women scar their bodies. If you see a Suri man with a scar, it ususally means that he has killed a member of a rival tribe.

Though invariably referred to by other Ethiopians as nomads the Surma along with all the other “nomads” of the region are no longer nomadic in the true sense of the word. They may once have been when people were far fewer and competition for grazing much less but nowadays they live a mostly settled life depending on cultivated grains (sorghum and maize) for the greater part of their subsistence. But their ideal is to herd cattle and this image of themselves as nomadic pastoralists persists in folklore.

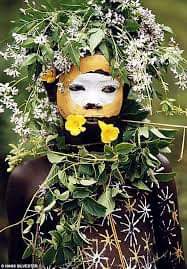

The Surma, like the Mursi, are well known for their stick fighting. At a fight, each contestant is armed with a hardwood pole about six feet long with a weight of just under two pounds. In the attacking position, this pole is gripped at its base with both hands, the left above the right in order to give maximum swing and leverage. Each player beats his opponent with his stick as many times as possible with the intention of knocking him down, and eliminating him from the game. Players are usually unmarried men. The winner is carried away on a platform of poles to a group of girls waiting at the side of the arena who decide among themselves which of them will ask for his hand in marriage. Taking part in a stick fight is considered to be more important than winning it. The men paint their bodies with a mixture of chalk and water before the fight.

Surma women, like Mursi women, wear lip plates. In her early twenties an unmarried woman’s lower lip will be pierced and then progressively stretched over the period of a year. A clay disc indented like a pulley wheel is squeezed into the hole in the lip. As it stretches ever-larger discs are forced in until the lip, now a loop, is so long it can sometimes be pulled right over the owner’s head. The size of the lip plate determines the bride price with a large one bringing in fifty head of cattle. The women make the lip plates from clay, colour them with ochre and charcoal and bake them in a fire.

Suri life

Suri villages range between 40 and 2,500 people. Village decisions are made by an assembly of the men, though women make their views known in advance of the debates. Village discussions are led by elders and the komoru – a ritual chief. The korumus all come from the same clan and are chosen by consensus.

Each household is run by a woman. The women have their own fields and dispose of the proceeds as they wish. Money they make from selling beer and grain can be used to buy goats, which they then trade for cattle.

The men of the village are divided by ‘age-set’: children, young men (tegay), junior elders (rora) and senior elders (bara). Each set has its role. Children start helping with the cattle when they’re about eight years old. The tegay age-set are unmarried and not yet known as warriors. They do the herding and earn the right to become young elders by their stick fighting and care of the cattle. Initiation ceremonies for those moving into the next age-set only happen every 20 or 30 years. The initiation ritual for the group becoming rora is particularly violent; the candidates are insulted by the elders, given menial tasks, starved and sometimes even whipped until they bleed.

Cattle are enormously important to the Suri. They bring status; when two Suri meet they’ll ask each other how many cows they have. Cows are a store of wealth to be traded, and a source of milk and blood. Bleeding a cow is more efficient than slaughtering it for meat, and blood can be drawn during the dry season when there’s less milk. An animal can be bled once a month, from the jugular.

The animals aren’t generally sold or killed for meat, though they are slaughtered for certain ceremonies. They are treated with reverence. Fires are lit to keep them warm and to protect against insect bites, they are covered with ash. Every boy is given a young bull to look after, and his friends call him the name of his bull. The Suri sing songs in praise of their cattle, and mourn them when they die.

The average man owns between 30 and 40 cows. In order to marry, he needs about 60 cows to give to his wife’s family. Suri men will fight to the death to protect their herd, and some risk their lives to steal from other tribes.

As well as cattle, the Suri trade. In the 1980s they smuggled automatic weapons from Sudan.

These days, the Suri are used to tourists visiting their villages but they have a very low opinion of their behaviour. It’s offensive, for instance, that people take pictures without asking permission and the Suri insist on being paid a fee. ‘They must be people who don’t know how to behave,’ one Suri told an anthropologist. ‘Do they want us to be their children, or what? This photography business comes from your country. Give us a car and we’ll go and take pictures of you.’

The Suri have some extremely painful rituals, including lip plates, scarification and dangerous stickfighting. Some anthropologists see these as a kind of controlled violence to get young Suris used to feeling pain and seeing blood. These are, after all, people who live in a volatile, hostile world, under constant threat from their enemies around them.

No one knows why lip plates were first used. One theory goes that it was meant to discourage slavers from taking the women. It’s undoubtedly painful. Once a girl reaches a certain age, her lower incisors are knocked out and her bottom lip is pierced and stretched until it can hold the clay plate.

‘We get a stick and make a hole’, explains Nabala, the wife of Bruce’s host. ‘Then we gradually make the hole bigger…. My lip was cut a long time ago. My brothers and father made me get it done. Without a lip plate I wouldn’t get married, and they’d get no cattle. My lip is big, Dongaley’s is smaller. My lip plate is worth 60 cattle. Hers is worth 40.’ A few girls are beginning to refuse to have a lip plate.

As well as lip plates, the girls of the village mark their bodies permanently by scarification. The skin is lifted with a thorn then sliced with a razor blade, leaving a flap of skin which will eventually scar. The men, meanwhile, scar their bodies to show they’ve killed someone from an enemy tribe. There are particular meanings assigned to these scars. One group, for instance, cuts a horseshoe shape on their right arm to indicate they’ve killed a man, and on their left if for a woman.

When it comes to religious beliefs, the Suri have a sky god, Tuma, an abstract divine force. There is no real veneration of the earth or earth spirits.

Suri stick fighting

Stick fighting is part martial art, part ritual, part sport. It’s seriously dangerous. ‘If you get hit in the stomach it can kill you,’ says Bargalu, Bruce’s host. That’s not to mention the danger if someone in the crowd decides to use their gun.

The fights take place between Suri villages, and everyone turns out to watch. The busiest time is just after the rains, when food is plentiful and there’s enough time and energy for fighting. There are something like 20 or 30 fighters on each side, who take turns to fight one-to-one. Most bouts – or donga – end in a draw after only a few blows have been exchanged. There are referees to enforce the rules – for instance, that you must never hit anyone on the ground.

Traditionally the stick fights were a place where young men could prove themselves to the girls and find a wife. But they’re more than just a meeting place. Dongas get young men used to the bloodshed they’ll face from the Nyangatom and other tribes, and provide the schooling a young man needs to fight for his tribe’s survival.

These days, guns are eroding the traditional controls. In the volatile atmostphere of the stickfight, shooting can easily break out. As one Suri woman puts it: ‘When our fathers were stick fighting no one went around shooting like this… Now all these young men they just pick up their guns. Bang! They’ll kill us all.’

Suri conflict

The dozen or so tribal groups in this part of southern Ethiopia are locked in mutual hostility. Fuelled by a steady supply of semi automatic weapons, the violence only gets worse.

Cattle raiding is a part of Suri life. Their herds are under constant threat, and they in turn regularly run raids on their enemies. Gazing land is under intense competition, particularly since the Sudan war pushed neighbouring tribes on to Suri lands. Gun battles rage during the dry season when the Suri move their herds south and fight for the pastures they need.

The Suri’s traditional enemies are the Nyangatom who, ten years ago, drove them from some of their traditional lands in a bloody conflict that has led to many deaths. Other enemies include the 70,000 Toposa, who live along the border with Sudan and often team up with the Nyangatom to raid Suri cattle and drive them off contested pastures.

Though hundreds of people have died in the conflicts in the region, the state authorities rarely provide any kind of formal justice. It’s a measure of how widespread weapons are that these days, an AK-47 is often part of the ‘bride price’ a man gives his new wife’s family.